I knew of only two other people in college who were as low on funds as I was. One was Therese, a dancer/choreographer who was so broke she auditioned for and became the Chicken at the Santa Cruz Boardwalk. The other was Chandra Garsson, who wanted to spend her time making art and was always scratching up money to pay the rent. Once she and I were so broke we had six dollars between us and we decided to blow it all on going to the movies—three movies in one evening, skipping from theatre to theatre in a small multiplex, a desperate, extravagant gesture (and the reason why “Gregory’s Girl” somehow loops into “Blade Runner” in my memory).

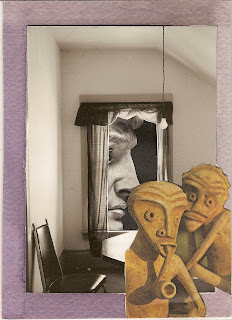

Chandra and I once spent several evenings designing postcard collages for money, which neither of us knew where to sell once we were done. Not knowing where to sell something I’ve produced has been a theme in my life since that time. Chandra has managed to do better in this regard—she has had exhibits and gallery openings, including Insomnia (Awakening), an exhibit sponsored by Pro Arts Gallery, and the city of Oakland. But her art has not been a constant or stupendous source of income for her.

Chandra is the only artistic person I’ve known since college who can still claim being an artist as her main identity. The rest of us have gone on to work as professors, teachers, editors, librarians, etc. Although she also dedicated much of her life to teaching art, she has consistently continued to produce visual art, and has held an exhibit almost every year since then.

The last time I saw her she was living in a section of an artists’ warehouse, the Dutch boy, in Oakland. Her junkyard chairs had been painted royal blue, with a golden skeleton sitting in each. Her couch was covered in canvas that had been painted beautiful, wild splatters of primary, secondary, and tertiary colors. The walls of her studio were covered with paintings, prints and collages, and corners held mannequins that were painted in keyed-up metallic colors and transformed into assemblaged surreal, other-worldly archetypes. She now lives in a smaller apartment by a lake in Oakland, having lost her battle with her former landlord, who wanted to turn the art studios into luxury apartments and office space. These days, she concentrates on smaller projects, including making jewelry, due to her smaller living space and her art studio being separate from where she lives.

For more on Chandra, see http://www.darksecretlove.com/chandra, a web page devoted to her art or her Facebook Fan page (which I started).

WH: What is the biggest difficulty for an artist starting out, as you did, after college? Did you have any connections with galleries or people who ran galleries? Did art professors you had help in any way?

Chandra Garsson: Poverty has always been my greatest challenge, along with exploitation by an almost wholly unregulated rental industry, both residential and commercial, legal and illegal. (I am fortunate in my landlord at my present art studio. It is an equitable, friendly relationship, with a very kind family.) I formed initial connections to galleries and museums. I did gain some renown, so I was at intervals contacted and recommended for exhibitions. While after graduation from BFA and MFA programs professors helped with letters of glowing recommendation, it was not always apparent from the many rejection letters I received over the years that images were viewed or the letters were read, perhaps because nothing was immediately translating for the recipients into dollar signs.

How did you forge ahead with an art career? Did getting a Master of Fine Arts degree help?

C.G: I’m not sure I did much “forging ahead,” except in the work itself, as must be distinguished from the career. Of course the MFA is helpful to most artists in their creative work, certainly it was to me. Knowledge is the only real power, and the discipline and exposure to voluminous visual and written materials, other artists, a constant tour of galleries, museums, artist’s studios, is beyond measurement.

Have you tried to do other things, or has art always been your main focus? (Did you ever consider being an art teacher? Is it difficult to get that gig?)

Have you tried to do other things, or has art always been your main focus? (Did you ever consider being an art teacher? Is it difficult to get that gig?)

C.G: I have been as one-pointed as any, and most artists are. I have devoted much of my life as an artist to teaching, a secondary yet fully compatible calling. The symbiotic relationship for the artist between creating and teaching worked especially well for me. I am a communicator, visually and verbally. Colleges have increasingly cut back what is offered to teachers since I have been in the job market.

What types of jobs/work have you done to supplement your income as an artist?

C.G: Aside from teaching, I have been a telemarketer and fundraiser, a waitress, switchboard operator, home health care-taker, baby-sitter, elder-sitter, day-care teacher, housecleaner, youth hostel cleaner, hospital cleaner, chai walla (in an office building in Amsterdam), dishwasher, kitchen worker at a Yoga Center, seamstress, department store cashier, and more…plus my favorite job, sitting in a campus Art Gallery, a very easy job I did for several years. In those days all that was required of me in this work was to watch and make sure nothing was stolen, greet people in a friendly manner, have conversations when desired by a visitor to the gallery. I conversed with friends, studied, dreamed up art projects, and sneaked the occasional catnap. I think this is the job that spoiled me for all other jobs. Sigh.

Has the economic downturn had any effect on the sales of your art, or is it always about the same?

C.G: Sales of my art have always been very up and down, most often down. The jewelry was doing better until the economic downturn, then sales fell off sharply. It seems to me the downturn has been coming on for longer than a decade, but that could just be me.

How would you describe and summarize your artwork in a few sentences?

How would you describe and summarize your artwork in a few sentences?

C.G: My artwork is largely autobiographical, hugely environmental, and wonderfully humorous in its willingness to address the darker, scarier aspects of the world around me.

How is it environmental?

CG: Largely, most of the components that go into my work would have ended up in a landfill. I estimate that I have saved at least 50 tons of trash, including industrial trash I found around my old studio at the warehouse in East Oakland. I’ve also used items from junk stores and flea markets, and things that people have found and have given to me, including dolls, mannequins, antique glass slides and animal bones. I have been poor in money and rich in materials!

When did you start using mannequins and dolls in your work?

C.G: I have always had an affinity with dolls, and mannequins to me, are large dolls. Dolls are, after all, sculptural representations at various stages of the human being, usually girls and women, which I was and am, respectively. They echo back to a helpless, vulnerable time in my life, when as a child, art and dolls were intricately intertwined as expression of an inner world that only I controlled. I suppose it could be said that this has never changed.

Are you doing more assemblage/collage than anything else, or do you do split your efforts between printmaking, painting and assemblage?

C.G: I’ve been doing all of the above except for printmaking, an art I have not practiced for many years. Lately I have been working with raw minerals and crystals such as Carnelian, Turquoise, Amber, Ruby, Prehnite, Moonstone, Garnet, Amethyst, Emerald and Flourite.

If I could wave a magic wand and affect your career, what would you most want to happen? Sales? Exhibits? Recognition? Something else?

C.G: 1. Recognition. 2. Something else (a greater sense of community between artists, myself included, and various systems of support for the artist). 3. Sales. 4.Exhibits.

What would you like to happen in your life and your art in the next ten years?

What would you like to happen in your life and your art in the next ten years?

CG: I would like to find good homes for all my artwork in the next ten years. They all need to be adopted into good families or to individuals that would take good care of them. A museum or several museums could house them all.

You told me once that you had transformed a public bathroom into a painting studio because it had good light. Are you still there, or how long were you there? Were you ever caught?

C.G: That was at Kala Institute, in Berkeley, where I made etchings and monotypes. It was a bathroom, large and light, custodially cared for. I kept my taboret and supplies in one of the stalls, and crawled under a door to unlock them, brought them into the center of bathroom to paint by the open window facing northwest. The sun filtered in afternoons, it was an idyllic place to paint. Almost no one used it, but one day someone came in, and told the director of Kala, Archana Horsting, about it. She confronted me, I explained, she listened, and reminded me to keep the supplies locked in the stall, out of the way. She reminded me to clean up all the paint each time. She sent me on my merry way. Archana is a fine person. Kala is a wonderful printmaking facility.

Do you feel that the artist is justified in doing anything; taking anything she needs, as long as she produces good art? (Does the artistic end always justify the means?)

C.G: Generally, there is a great deal to the notion of artistic license, as long as no one, including the artist, is hurt. Your use of the word “anything” is more than a bit open-ended. Come to think of it, the word “take” is more than a bit suspect. I have always striven for the quality of harmlessness. I am quite a moral person, one could say didactic, in the messages of my work and life.

Have you known artists who have achieved fame, undeservedly, because of who they knew or who they slept with?

C.G: Goodness gracious, girl! Um, let’s just say that as an artist who has not made it to the top, I do not personally know artists at the top, so I do not know, and let’s leave it at that. If it were to happen, I would view it as unfair exploitation of the artist, by one with far greater power than the artist in our world ever has, unless a jolly good time was had by both parties.

Has doing yoga had any effect on your art?

C.G: Yoga has had a profound effect on my art, and my art has had a profound effect on my yoga practice. They are compatible practices—one informs the other, both are enhanced by the dual focus.

How about being Jewish?

CG: Being culturally, racially and spiritually Jewish is also compatible with yoga and art.

And being feminist?

CG: One of my professors, Sam Richardson, told me several times in grad school that my work is strongly feminine. I have realized since, over the years, that my work is emphatically feminist—which is completely compatible with being Jewish, environmental and doing yoga.

What keeps you going as an artist?

I have important things to say and art is the best way for me to communicate those things to the world.